A Chance Encounter

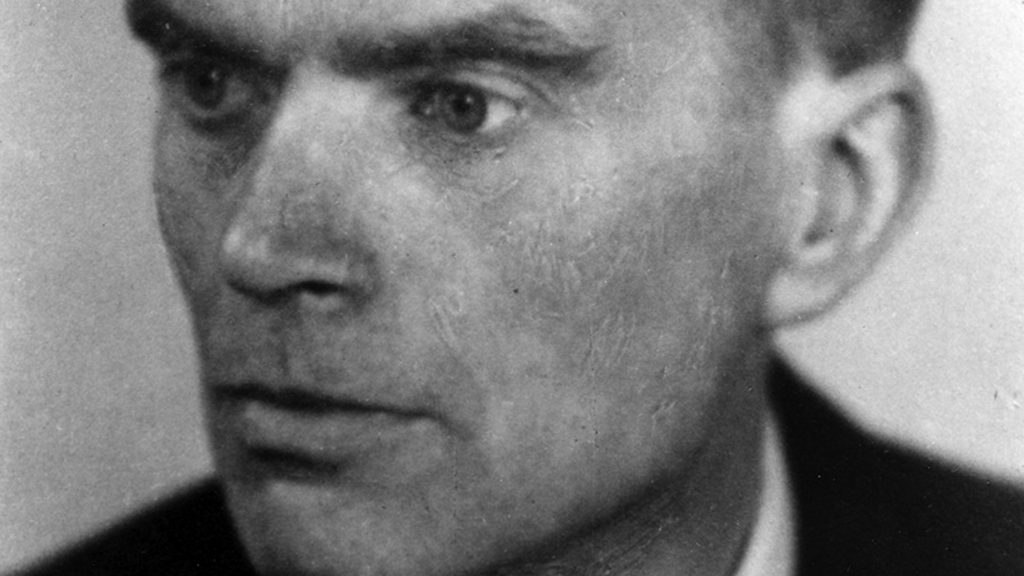

I had never heard of Ernst Lohmeyer until I was in my late twenties. I came across his name in the same way I came across many names at the time, as another scholar whom I needed to consult in doctoral research. In the mid-1970s I was writing my doctoral dissertation on the Gospel of Mark in then McAlister Library at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. A premier commentary on Mark at the time was Ernst Lohmeyer’s Evangelium des Markus (Gospel of Mark), a commentary that proved unusually helpful in my doctoral research. I knew nothing about its author, but the front matter of the book said the following:

Although it is a joyful occasion to welcome the second edition of Prof. Lohmeyer’s Commentary on Mark, it is at the same time regretful for both academy and church that the author himself can no longer undertake its publication. His hand-written changes on which the new edition is based reveal how continuously he labored to improve and expand his book, until a higher power carried him off to a still-unresolved fate.

Evangelium des Markus

The note about Lohmeyer’s mysterious disappearance stayed with me by the sheer power of its intrigue. In 1978 I received my Ph.D in New Testament, and in the following summer I returned to East Germany as translator for a small group of American Christians visiting East German congregations. We were in Greifswald, the city where Lohmeyer was arrested and imprisoned. In our final meeting, while enjoying Kaffee und Kuchen––coffee and cake––in the basement of dicke Maria––“Fat St. Mary”––I suddenly recalled that Greifswald was where Ernst Lohmeyer had “mysteriously disappeared.” Until that moment I had not made this connection. His fate and the city of Greifswald suddenly seemed like two live wires that I should try to connect. “Isn’t Greifswald where Ernst Lohmeyer taught?” I interjected suddenly. “Does anyone know what happened to him?”

The warmth and conviviality suddenly dissipated as though someone had thrown a light switch. I had no idea why. The pastor of Fat St. Mary, Dr. Reinhard Glöckner, did. He rose, brought the meeting to a hasty and awkward conclusion, and said to me, “Jim, let’s take a walk.” In a society where listening devices were placed in radios and TVs, in light sockets and under reception counters, where social settings such as this invariably had listening ears, a walk usually guaranteed privacy. We walked along Brüggstrasse to the point where it exited through the old city walls. There we took a right and walked along a gravel path. Glöckner broke the silence. “Jim, we cannot mention the name of Ernst Lohmeyer in this city!” I had been raised in a society where an overly free inquiry might offend social etiquette, but it would not kill a healthy meeting. Why would a question cause such offense? Glöckner explained why. “Lohmeyer disappeared at the hands of the communists,” he said in veiled exasperation. “He was certainly killed by them, although we don’t know any details. People who are liquidated by the communists are considered enemies of the state, and whoever inquires about their fate is considered an accomplice. Accomplices are enemies of the state! Your question jeopardized everyone in the room this afternoon!”

Pastor Glöckner’s reprimand left me profoundly divided: I regretted endangering others by what I said, but I was indignant at what had happened to Lohmeyer. The murder of a man of Lohmeyer’s character and stature seemed a particular evil, but worse still was the forty-year attempt of the communist government of East Germany to expunge all memory of him. Behind the wall on our right was a row of tired buildings. One of the more prominent buildings was a four-story Orwellian structure constructed of red brick with small windows high in its walls. This building had been a prison. I did not know it at the time, but in this prison Lohmeyer spent the last months of his life, and in its courtyard, he may have met his death. I made a silent resolution. It was hazily formulated, and I could not have expressed it clearly, but it was resolute. If the opportunity ever presented itself, I would try to get to the bottom of Lohmeyer’s fate.

In 1989 the Berlin Wall came down, and communist East Germany was history. Finally, after fifty years, the mysterious circumstances related to Lohmeyer’s disap-pearance and death could be investigated. I received a grant from the German Academic Exchange Service to investigate his mysterious death and disappearance, and I returned to Germany to make a nuisance of myself in attempting to solve a murder mystery.

Who was Ernst Lohmeyer?

Perhaps the best way to think about the lives of others is not simply when they lived, where they lived, or what they did, but rather what made them significant, why should they be remembered, and in what ways they might be meaningful models for our own lives. Four aspects of Ernst Lohmeyer’s life have greatly affected my life, even changed it, and I share them with you in hopes both to inform and perhaps influence you as well. The four points of significance I wish to note are Lohmeyer’s role as a scholar-theologian, his courageous witness against both Nazi and Soviet-communist oppression, his leadership in times of crises, and his commitment to his marriage vows to his wife Melie.

Lohmeyer: Scholar Theologian

Everything in life prepared Ernst Lohmeyer to be a scholar-theologian. Born in 1890 into a pastor’s family in northern Germany, he received not only a premier education in a German gymnasium, but his father’s additional tutoring in Greek, music, philosophy, and theology. He was better educated when he entered the universities of Tübingen, Leipzig, and Berlin than I was when I graduated from university. By the time he was twenty-four, he had earned two Ph.Ds, one in theology at Berlin (1912), and a second in philosophy at Erlangen (1914). (A note about the intellectual climate at the University of Berlin at the time may be of interest here: In the forty years between 1900 and 1940, thirty-two Nobel prizes were awarded to professors at the University; in the forty following years from 1950-1990 when the University was in the communist sector of East Berlin, only one Nobel prize was earned at the University of Berlin. That tells you something about the influence of communism on intellectual creativity and productivity.) Lohmeyer continued his scholarship during five and a half years as soldier in World War I, studying and writing from 5–7 every morning in his tent. When he was released from military duty in October 1918, he published a book on the Roman emperor cult and received a call as Professor of New Testament at the University of Heidelberg. He received an honorary doctorate from Heidelberg three years later and was called to succeed Rudolf Bultmann as professor of New Testament at the University of Breslau, the easternmost city of then-Germany (today it is in Poland). Lohmeyer remained at Breslau until the mid-1930s, where he published eight scholarly books, twenty-two scholarly articles, and formed friendships with some of Germany’s top Jewish intellectuals—including Richard Hönigswald, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, and Jochen Klepper. In 1930 he was named Rektor Magnifizenz of the University of Breslau. Ernst Lohmeyer was a theological supernova. He was one of the leading intellectual stars in a star-studded sky of German intellectuals.

What made Lohmeyer a great theologian?

• He was an independent thinker. He thought for himself rather than following trends, he mastered original sources rather than repeating secondary literature. His writing is not derivative, but alive with free and fresh insights.

• His primary theological objective was always the meaning of the Bible, especially for theology and the church, rather than simply in his history, or sociology, or theories of textual development. He strongly resisted the dismemberment of the New Testament according to source theories that dominated early twentieth-century German Biblical scholarship.

• He was adamant about the significance of Jesus for the New Testament, theology, and the church. This sounds obvious today, but it was not then: leading scholars like Rudolf Bultmann and Martin Dibelius relegated Jesus to the Old Covenant, maintaining that Christianity started not with Jesus but with Paul and the early church.

• Lohmeyer was convinced that Christianity was the fulfillment of Judaism, not its enemy. The New Testament could not be rightly understood apart from the Old Testament. Here too he was a pioneer, because the hyper-Lutheran influence on New Testament studies, especially as it was distorted by Nazism, caused many German theologians to look on the Old Testament with disdain and on Jews with hatred.

Lohmeyer’s command of original sources was phenomenal, his writing style was imaginative and bold, he was hugely productive, and he was courageous in opposing trends that desired to shape the academic life and the church into organs of a totalitarian state. Had his life fulfilled his trajectory, he would have been one of Germany’s most famous scholars of the 20th century . . . but I wouldn’t have written a book on him. I would not have needed to, because he would have been as well-known as Bultmann, and second only to Karl Barth.

Nazism

In a violent attempt to wrest Germany’s reputation from infamy following World War I, Adolf Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, and especially its humiliating War Guilt clause, and rearmed Germany to withstand the rising tide of Russian Bolshevism. Nazism arose to regain German pride and German power. Nazism glorified the myth of the German Volk and demonized outsiders, foreigners, immigrants, international relat-ions, and Slavs, Gypsies, and above all Jews. Germany defined itself and its destiny on the basis of fear. Fear leads to distortions of reality, which in turn leads to irrational and sometimes catastrophic responses to reality. Germany descended into inner migration and self-imposed isolation. Nazi Germany built walls, both physical and ideological. Slogans replaced reasoned speech; extremism replaced measured and thoughtful discourse; fears replaced facts; moderation and the middle ground were abandoned; seeking to understand adversaries was called cowardice and attacked by both the extremes of right and left; propaganda––the original “fake news”––displaced truth; power replaced justice. “Germany First,” “Germany Alone,” the triumph of nationalism and maligning of internationalism were the Nazi rally cries. Everything outside the closed inner-circle of Germany and German Volk was an enemy, destined for annihilation.

Lohmeyer was clear-sighted and courageous in realizing that such political madness and malignancy required more than hand-wringing or pamphleteering. It required decisive action. He joined the Confessing Church, and was indeed one of the few professors to do so. In a public protest against Nazism, he signed the Confession and Constitution for German Professors. He fought to retain Jewish professors at the University of Breslau, and to protect them from assaults by the National Socialistic German Student Association. When Nazi students stormed the university lecture halls in an attempt to attack Jewish professors––a scene not dissimilar to the attack on the Capitol last January––Lohmeyer and Rosenstock-Huessy strung barbed wire across the stairway to protect Jewish professors on the third floor.

Ernst Lohmeyer resisted Nazism at its deepest and most malevolent level, its anti-Semitism. He wrote a courageous letter to Martin Buber, whose book “I and Thou” was destined to be one of the most influential books of the twentieth century. Buber was a Jewish polymath––narrator of the tales and stories of the Hasidim, translator of the Hebrew Old Testament into elegant German, recipient of the first Frankfurt Prize, the highest award Frankfurt awards German citizens. In 1935 this great savant and humanitarian was stripped of his citizenship, of all his honors and degrees, and placed under house arrest. Gerhard Kittel and Walter Grundmann, both Nazi theologians, wrote personal attacks against Buber. Lohmeyer weighed in on the side of Buber with a letter of advocacy that, in my judgment, ranks among the most significant statements of theological social righteousness of the Twentieth Century. He summarized the spirit of the times thus: “Every assured consensus has vanished, discourse is now polarized and combative.” Regarding the church’s complicity with Nazi anti-Semitism, Lohmeyer wrote: “We have never drifted further from the Christian faith than we have at present. … It is a bitter experience for me that in our Christian and theological publications one so easily succumbs to politically tainted slogans. … More bitter still is that once the defamation is politically or socially carried out, no theologian and no churches speak the word of their Master to the victim, ‘You are my Brother!’. … I hope that you will be in agreement with me in this, that the Christian faith is Christian only insofar as it bears the Jewish faith in its heart; I do not know if you will be able also to affirm the reverse, that the Jewish faith is Jewish only insofar as it preserves within itself a place for the Christian faith.”

Martin Buber was expelled from Germany. Lohmeyer himself was stripped of his university post at Breslau, where he had been both president and brought international acclaim to the University. An unsuccessful attempt was even made to strip him of his two doctoral degrees. Buber and Lohmeyer both became exiles in Germany––Buber as a Jew, Lohmeyer as a Christian.

Here is what I love about Ernst Lohmeyer, and what I hope you will love as well. He did not enter the fray on the basis of winning, but on the basis of the moral and theological truth at stake. The idea of contending for issues on the basis of their winnability never crossed his mind. He was not a utilitarian who measured engagement on the basis of outcome. He was an unalloyed virtue ethicist, an idealist, a Platonic idealist, a Kantian idealist, and above all, a Christian idealist who engaged issues on the basis of virtue and merit, and on nothing else. The battle worth fighting was not the battle that could be won, but the battle that virtue––truth, justice, love for the other––demanded one to fight, irrespective of outcome. Lohmeyer said to Nazism and communism what Martin Luther said to Emperor Charles V, “Here I stand! I can do no other!” The one and only virtue for Lohmeyer was always to live––and, if necessary, to die––as a man worthy of the freedom that was both given and required of the tradition of Christian humanism.

Leadership in Times of Crisis

Ernst Lohmeyer was an unlikely leader. He made no effort to surround himself with admirers, formed no cliques or “schools of thought,” and paid little attention to public acclaim. He was frequently seen as an Einzelgänger––an independent or loner. Despite this––or perhaps because of it—he was twice elected to university presidencies. In Germany, university presidents are elected by fellow faculty members (and not by boards of trustees, as in America). Lohmeyer was twice chosen by faculty votes to pilot universities through the most perilous waters of the twentieth century––through National Socialism at the University of Breslau and through Soviet communism at the University of Greifswald. In each instance he was chosen to lead because he possessed two qualities that I believe are always and everywhere desirable in leaders, especially in times of danger and crisis: he was intellectually formidable, and his character was unimpugnable. Ernst Lohmeyer was a man of intelligence and integrity, of learning and respect.

When leaders speak truth, when they display courage, when they unmask tyranny for what it is, they have a redemptive effect on the communities that look to them as leaders. This is especially true in a university setting where students look to teachers and administrators with a trust that the ordinary populace does not expect of politicians and celebrities.

Lohmeyer’s inaugural address as president of the University of Breslau is an example of such leadership. Lohmeyer was named president of the university in 1930, fully three years before Hitler was sworn in as chancellor of Germany. Nevertheless, the university systems throughout Germany, including their administrations and faculties, were already capitulating to Nazi ideology. The German university embraced Nazism earlier and more completely than virtually any other segment of German society. Those who heard Lohmeyer’s inaugural address at Breslau surely expected him to declare that the history of Germany was reaching its crowning goal in National Socialism. Lohmeyer called upon the power of history, however, to turn the university from such madness. Midway through his address he hit Nazi supporters and sponsors in their solar plexus. One civilization and people, he declared, more than all the others––more than Babylon, Greece, Rome, Egypt, India, Persia, Germania, China, Mexico ––has tutored the world in the meaning of faith and history. That people is “the Israelite-Jewish people,” to whom God said, “Those who were not my people, I will call my people; and those who were not loved, I will call my Beloved” (Romans 9:25). Lohmeyer’s German is important here, for the German word for “people” is Volk––a word that had assumed virtual sanctity in National Socialist propaganda. The small and seemingly insignificant Jewish people bore witness to a synthesis of faith and history that occurred nowhere else in the world. From this marginal Volk, the world was introduced to the saving faith of the individual, faith reduced to one, the Messiah not only of Israel but also of the world. That one individual came from the Jewish people. He alone is the consummation of faith and human history, as the Gospel of John attests, “And the word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we saw his glory.” The “Word become flesh,” declares Lohmeyer, relieves the world of looking for saviors and messiahs elsewhere than in Jesus Christ.

Lohmeyer’s inaugural address was a tour de force of intellectual history. It resembles C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man in grounding a moral universe in the deepest roots of human history. But it was more than a survey of the past. Without once mentioning “National Socialism,” or its tenets, slogans, or caricatures, Lohmeyer subjected the Nazi myth of hate and fear to the crushing weight of historical reality and truth. The individual cannot be dissolved into the Volk. The state cannot be deified. Macht—raw power—cannot be glorified as the chief virtue of the state. The historical and religious witness to the eternal moral order cannot be replaced by arbitrary values of a false ideology. Finally, and above all, the testimony of God to the gospel of Jesus Christ has been revealed solely and ineluctably through “the Israelite-Jewish religion,” for “salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22). The object of Nazism’s poisonous venom and brutal violence is, ultimately, the very cradle of Christianity. Lohmeyer’s inaugural address at Breslau was a devastating intellectual and theological denunciation of Nazism even before it officially came to power.

Lohmeyer did more than speak truth to tyranny, however. As I noted earlier, he also enacted it. When two of his students removed a Nazi hate-Jew flyer from the Theology Department bulletin board, the University of Breslau required Lohmeyer to identify the students. Lohmeyer refused to do so, knowing that their identification would result in their expulsion from the university and perhaps their incarceration in a concentration camp. In consequence of Lohmeyer’s refusal to divulge the names of the two students––siblings named Hanna and Robert Bedürftig––the university subjected him to the humiliation of a public apology before the entire student body.

In summer 2019 I received a letter from a seventy-eight year old woman in Poland. This is what she wrote. “I have just finished reading your biography of Lohmeyer entitled Between the Swastika and the Sickle, and it completes an unfinished circle in my life. For the last fifty years I have had three photographs on my bed stand—one of my mother, one of my father, and a third of Ernst Lohmeyer. I never knew what happened to Professor Lohmeyer. He was the professor who saved his student assistant Hanna Bedürftig, and her brother Robert, when they removed the flyer from the Theology Department bulletin board. Hanna Bedürftig later became my mother, and her brother Robert my uncle. As her daughter, I feel my own life is in a very real sense also indebted to Professor Lohmeyer.”

Love

Lohmeyer married the first woman he dated, Melie Seyberth, who was the true love of his life. It was an uncommon marriage, and it was expressed in uncommon bonds. Their courtship began during World War I when Lohmeyer, a soldier on the Eastern front, wrote letters to Melie back in Germany. Thenceforth, but especially in their nine-and-one-half years of separation during World Wars I and II, letters became a primary medium of love between Ernst and Melie. Theirs was a relationship––to rely on a common expression at Whitworth University––of “mind and heart.” No couple better exemplified Aristotle’s description of friendship as two bodies with one soul than Ernst and Melie Lohmeyer. Writing was as natural to them as walking and breathing, and a medium of their holistic love that no other medium satisfied. In the five-and-one-half years when Ernst and Melie were separated during World War I, they wrote 2100 letters to one another, all hand-written, and most between two and four pages long.

But true love is seldom unchallenged, the Lohmeyers’ included. Lohmeyer’s battle in Breslau to defend both his professorship and the university from Nazi devasta-tion strained their marital relationship. His four-years absence in World War II further strained it. When he returned home to Greifswald after two-years’ absence on the Eastern front in Russia, Lohmeyer’s visage was so altered that Melie did not recognize him, and when she did, she was so distraught that she did not embrace him. In his effort to reopen the University of Greifswald in the Russian Sector of East Germany after the war, Lohmeyer found himself embattled in defense against a communist takeover of the University. Melie and he were not always agreed on how to deal with the Soviet attempts to usurp of the University of Greifswald, of which Lohmeyer was president. In retrospect, Melie was more often correct in her assessment of the Soviets than Ernst was. When Lohmeyer was arrested by the NKVD the night before he was to be installed as president of the University of Greifswald on February 15, 1946, his physical relationship with Melie ended forever. They never saw each other again.

Separated, fated to die, and without opportunity to mend the torn fabric of their relationship, Lohmeyer smuggled one letter out of prison to Melie––a ten-page letter, written in minuscule handwriting that is barely legible. The purpose of the letter was not to report on prison conditions or on his interrogations, trial, mistreatment, and sufferings. The purpose was to express his undying love for Melie and restore their marriage. He had experienced in prison what he considered a miracle––“the finger of God,” as he called it. The finger of God was the strength to reconcile their marriage. “Would God have taught me all He has in prison simply to allow it to perish behind these prison walls?” he asks. He ends his long letter––the final letter of several thousand he wrote to Melie in his life––with this line: “If only you will still love me, if only I can be certain of your love? Then it is again possible that you will embrace me in your arms!” The reference to “embrace” recalls Mellie’s failed embrace when he returned from the Russian front. In the handwritten original of Lohmeyer’s letter, it is impossible to tell whether he punctuated the last sentence with a question mark or an exclamation mark. Melie, fortunately, made a typescript of Ernst’s handwritten letter for her children to read. In her typescript, she supplies the final punctuation—an exclamation mark! That exclamation mark is her final embrace of Lohmeyer, that both she and Ernst longed for. Forgiveness and reconciliation are possible even in separation.

The Sovereign “Finger of God”

Ernst Lohmeyer was born and educated at the apogee of German civilization. With the rise of Nazism in Germany, however, which was followed by Soviet communism in East Germany, Lohmeyer was fated to end his life at the nadir of German civilization. He was witness to the most catastrophic events of modern history, including the descent of his noble German civilization into barbarism. Lohmeyer’s uncommon abilities destined him to play leading roles in the dramatic events of his time, but his abilities did not equally destine him or anyone else in preventing or controlling or to any significant degree averting the catastrophes which befell his nation, its institutions, his church, and his own life. But if greatness––at least Christian greatness––consists not in determining destinies but rather in faithfulness to Jesus Christ in the unheralded duties of charity and personal sacrifice which present themselves in all times and walks of life, then Ernst Lohmeyer was not only a witness in his own time but is also a witness for our time and beyond. Like the Apostle Peter, who in early life dressed himself and went where he pleased, but in later life was called to go where he did not want to go, so too Ernst Lohmeyer’s early years of scholarly achievement and promise yielded in mid-life to the higher summons to places and duties that he did not choose but which he could not avoid if, like Peter, he too was to heed the call of Christ ––“Follow me” (John 21:18–19).