People are always shouting they want to create a better future. It’s not true. The future is an apathetic void of no interest to anyone. The past is full of life, eager to irritate us, provoke and insult us, tempt us to destroy or repaint us. The only reason people want to be masters of the future is to change the past. They are fighting for access to the laboratories where photographs are retouched and histories rewritten.

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is,

seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

was incarnate of the Holy Spirit

and the Virgin Mary

and became truly human.

For our sakehe was crucified

under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life

who proceeds from the Father,

who with the Father and the Son

is worshiped and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic

and apostolic church.

We acknowledge one baptism

for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come.

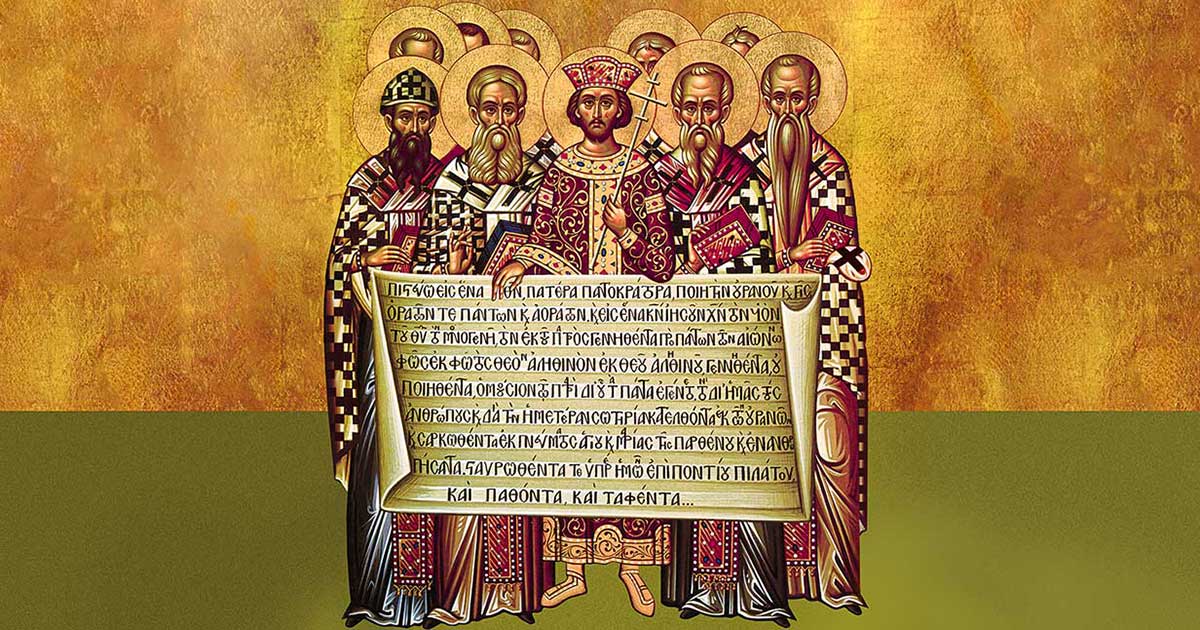

The first great ecumenical council of the church met in A.D. 325 at Nicaea, a small city near the imperial residence at Nicomedia. The gathering of three hundred bishops from across the church was called by the emperor Constantine to deal with a dispute that threatened the unity of the church (and the empire). The origins of the dispute are complex, but the crisis that necessitated the council centered on the divergent views of Arius, a priest in Alexandria, and his bishop, Alexander.

Why should contemporary Christians care about a seven-teen hundred-year-old controversy, and why should we study the dispute’s resolution in what we now know as the Nicene Creed? The fourth century council’s determination was not universally accepted then, and divergent views linger still, living unrecognized among church members and their ministers. The issues addressed at Nicaea are not merely ancient history, but contemporary issues throughout the church. In the memorable words of William Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”[1] Perhaps careful attention to the Creed articulated at Nicaea in 325 can, in 2026 and beyond, inform, reform, and deepen the church’s faith and life by shaping congregational preaching and teaching.

The Nicene Creed is crucial today not only for what it affirms, but for what it denies. “If the Yes does not in some way contain the No,” says Karl Barth, “it will not be the Yes of a confession . . . If we have not the confidence to say damnamus [what we refuse], then we might as well omit the credimus [what we believe].”[2] Christopher Morse puts the matter less dramatically when he asks rhetorically, “Are there some things that Christian faith refuses to believe? And if so, how do we come to recognize what they are?” Knowing that those questions are too infrequently asked, Morse goes on to say that “It is far more customary to speak of beliefs of the Christion faith than of disbeliefs of the Christian faith.[3]

Denials that dwell beneath affirmations are sometimes made explicit, as in The Theological Declaration of Barmen’s six evangelical truths. The first of these begins with Scripture: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life: no one comes to the Father but by me.” (John 14:6). “Truly, truly, I say to you, he who does not enter the sheepfold by the door but climbs in another way, that man is a thief and a robber. … I am the door; if anyone enters by me, he will be saved” (John 10:1,9). Following Scripture is the affirmation and its denial:

Jesus Christ, as he is attested for us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God which we have to hear and which we have to trust and obey in life and in death.

We reject the false doctrine, as though we could and would have to acknowledge as a source of its proclama-tion, apart from this one Word of God, still other events and powers, figures and truths, as God’s revelation.[4]

The Confession of Belhar follows the same pattern, following statements of belief with denunciation of false doctrines. The affirmation that “God has entrusted the church with the message of reconciliation in and through Jesus Christ” necessitates the rejection of any belief or practice that: sanctions in the name of the gospel or of the will of God the forced separation of people on the grounds of race and color and thereby in advance obstructs and weakens the ministry and experience of reconciliation in Christ.[5]

The most dramatic (and sadly ignored) instance of the affirmation/denial pattern is found in the Westminster Larger Catechism’s treatment of the Ten Commandments. Each begins with an elaboration of the duties required by the commandment before cataloguing the sins forbidden. Westminster’s exposition of the eighth commandment, “Thou shalt not steal,” concludes its list of duties by urging us to “endeavor by all just and lawful means to procure, preserve, and further the wealth and outward estate of others, as well as our own.” Only then does the Catechism deal with the sins prohibited by the commandment not to steal, including in a lengthy list, man-stealing [the slave trade], fraudulent dealing, oppression, vexatious lawsuits, and inordinate prizing and affecting worldly goods.[6]

The Nicene Creed confesses faith in the One God, Father Son and Holy Spirit. What denials lie beneath that foundational affirmation? Contemporary attention to the Creed requires us to be aware of cultural beliefs, religious as well as secular, that we must deny because of what we believe. Affirmation and denial are not only matters of academic interest, but also at the heart of pastoral and congregational proclamation. The Nicene Creed begins with the affirmation, “We believe.” In every community gathered around Table, font, and pulpit, vital witness to the truth of the gospel requires clarity concerning opinions and practices that twist, pervert, or deny the gospel. An institutionalized church––institutionalized denominations and their congregations––is always in danger of placing the gospel in the service of its own desires, purposes, and plans. Serious, sustained attention to the Creed can bring the core of the gospel to the center of denominational and congregational faith and life.

The Arian Controversy

The dispute between Arius and Alexander focused on the very being of God––specifically the unity of the Son and the Father. The alternatives were stark: Is the Son fully God, commensurate with the Father? Or is the Son sub-ordinate to the Father, a created being? Arius was a good thinker who was determined to advocate belief in the one and only God in the face of the surrounding culture’s pervasive polytheism. He became convinced that the oneness of God could only be preserved by excluding all distinctions from the divine nature. Thus, Arius taught that belief in God’s oneness necessitated a lesser status for Christ. While the Son was a “divinity” he was a created being, subordinate to the one and only God.

“We know there is one God,” said Arius and his followers, “the only unbegotten, only eternal, only without beginning, only true.”[7] This strong affirmation of the one true God led the Arians to assert a lesser, dependent status for the Son: “He is neither eternal nor co-eternal nor co-unbegotten with the Father, nor does he have his being together with the Father.”[8] The response from Arius’ bishop, Alexander, was swift and strong: “What they assert is in utter contrariety to the Scriptures and wholly of their own devising. … Hence [in their view] the Word is alien to, foreign to, and excluded from the essence of God; and the Father is invisible to the Son.[9]

The controversy that necessitated Nicaea is not confined to the fourth century. Every pastor has heard parishioners say that while they believe in God and consider Jesus a great teacher and exemplar, they do not believe that he is God, a god, or divine. Perhaps a more subtle rendition is the emphasis on Jesus in much contemporary liturgy, hymnody, preaching, and devotional writing, paired with diminished reference to Christ’s salvific and lordly mission.

Scholarly engagement in repeated quests for the historical Jesus have little room for theological understanding of his crucifixion, and none for resurrection, ascension, and universal lordship. It has also become commonplace to dismiss Nicene faith as merely one opinion that became established as dogma by the winners of a human debate. A religious implication of the idea that “history is written by the victors” is the notion that the church must now overcome oppressive orthodoxy by recovering the suppressed voices of silenced theological minorities. Elaine Pagels, for instance, contends that gnostic gospels were suppressed and forcibly eliminated by an ecclesiastical apparatus that would not tolerate the idea that people could find God by themselves. Similarly, the church’s creeds are dismissed as ecclesiastically enforced suppression of theological pluralism.[10] The Arian controversy is not dead; it is alive and well and lurking in all corners of church life.

The Rule of Faith

The history of the Nicene Creed has often been told as if the primary business of the first centuries of the church was promulgating doctrine, sorting out true faith from heresy by imposing universal requirements of truth for the ages. Creedal history has also been presented as the fusion of imperial and ecclesiastical politics to eliminate diversity by establishing Constantinian uniformity in church and empire. Both descriptions grow from the mistaken notion that the Creed was “composed” in 325, emerging full blown from the deliberation of the church’s bishops.

The Nicene Creed was not an innovation, created ex nihilo, for it was deeply rooted in the church’s baptismal life: “Go, therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit (Mt 28:10). The substance of the Nicene Creed emerged from summaries of Christian faith taught to new believers by their local bishops and confessed at their baptism. Because the summaries were specific to each bishop’s location, their articulation varied from place to place. Yet they were not substantively divergent, for all were instances of what came to be called the regula fidei––the rule of faith––that provided the church with a norm of Christian belief and practice.

In circa 180–192, well over a century before the Council of Nicaea, Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons in Gaul, set forth an already traditional summary of Christian faith:

The Church, indeed, though disseminated throughout the world, even to the ends of the earth, received from the apostles and their disciples the faith in one God, the Father Almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth and the seas and all that is in them; and in the one Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who was enfleshed for our salvation; and in the Holy Spirit, who through the prophets proclaimed the dispensations of God––the coming, the birth from a virgin, the suffering, the resurrection from the dead, and the bodily ascension into the heaven of the beloved Son, Christ Jesus our Lord, and his coming from heaven in the glory of the Father to restore all things, and to raise up all flesh of the whole human race, in order that to Christ Jesus, our Lord and King, every knee should bow in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess him, and that he would exercise just judgment toward all … . The Church, though disseminated throughout the whole world, carefully preserves this proclamation and this faith which she has received, as if she dwelt in one house. She believes these things as if she had but one soul and the same heart; she preaches, teaches, and hands them down, harmoniously as if she possessed but one mouth.[11]

A few years later, ca. 195–210, a priest in North Africa, Tertullian, gave a striking rendition of the regula fidei:

The Rule of Faith––to state here and now what we maintain––is of course that by which we believe that there is but one God, who is none other than the Creator of the world, who produced everything from nothing through his Word, sent forth before all things; that this Word is called his Son, and in the name of God was seen in divers ways by the patriarchs, was ever heard in the prophets and finally was brought down by the Spirit and Power of God the Father into the Virgin Mary, was made flesh in her womb, was born of her and lived as Jesus Christ; who thereafter proclaimed a new law and a new promise of the kingdom of heaven, worked miracles, was crucified, on the third day rose again, was caught up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of the Father; that he sent in his place the power of the Holy Spirit to guide believers; that he will come with glory to take the saints up into the fruition of the life eternal and the heavenly promises and to judge the wicked to everlasting fire, after the resurrection of both good and evil with the restoration of their flesh.[12]

Tertullian emphasized the foundational significance of the rule of faith by concluding, “Provided the essence of the Rule is not disturbed, you may seek and discuss as much as you like. You may give full reign to your itching curiosity where any point seems unsettled and ambiguous or dark and obscure.”

Some matters did remain unsettled, ambiguous, and obscure, and curiosity—both helpful and harmful—has been a hallmark of theological inquiry throughout the life of the church. But while expressions of the rule of faith, the catechetical teaching of bishops, and the baptismal confessions of believers were not fixed, they all summarized the same scriptural story in the familiar three-part structure with clauses about the one God, Father Son and Holy Spirit. The bishops did not gather at Nicaea with blank slates, but as pastors who knew and proclaimed the faith of the church.

The Rule of Faith did leave one matter “unsettled and ambiguous” if not “dark and obscure.” Both Arius and his bishop Alexander agreed with the Rule’s teaching of “the one Christ Jesus, the Son of God” and that “the Creator of the world, who produced everything from nothing through his Word, sent forth before all things; that this Word is called his Son.” The question was whether the Son was God together with the Father, or a created instrumentality of the Father. Both could point to Scripture to buttress their contentions. On the one hand, “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30, passim), on the other hand, “I go to the Father; for the Father is greater than I” (John 14:28, passim). Citing bits of Scripture was insufficient to answer the primary question that had to be answered by the council: “Is the Son truly God?”

The Council and the Creed

Today, Protestant councils––general assemblies, synods, and conferences––are brief meetings of strangers called to decide hundreds of proposals and set denominational policies and procedures. Delegates leave the assemblies with no continuing responsibility for the decisions they have made, few of which are known by members and ministers, and most of which are soon forgotten.

The Nicene council consisted of bishops, many of whom knew or knew of the others. They met from May to July 325 to consider the status of the Son of God. The issue, dramatized by the Arius/Alexander dispute was not new. Varieties of viewpoints had been in the air for centuries. It had seemed to be enough to believe and teach Father, Son, and Holy Spirit without the need for more theologi-cal precision about their essential relationship. The Arian dispute required a measure of precision, however.

The council’s deliberations led to a statement that was meant to settle the issue at hand yet not legislate doctrine for the whole church. There was no centralized ecclesiastical structure to make and require decisions that applied to all. The creed of Nicea became known and accepted gradually by virtue of its persuasive strength, and that took decades. Nicaea was only the beginning of a series of ecumenical councils called to deal with the implications of its confession that the Son is truly God.

The Creed dealt with the unity of Father and Son, but its thinking about the Spirit was confined to a terse (not even a sentence), “and the Holy Spirit.” Only with the council of Constantinople in 381 did the church address the question, “Is the Holy Spirit truly God?” Fifty years later another council convened at Ephesus to answer the question, “Is Jesus Christ truly human?” Then, only twenty years later, a council at Chalcedon was called to wrestle with alternative ways of understanding Christ’s true divinity and humanity: are divinity and humanity blended, or separate, or alternating, or something else? Nicaea was the beginning of a long, winding road that led eventually to theological consensus concerning our understanding of the One God, Father Son and Holy Spirit.

The enduring significance of the Nicene Creed does not lie in dissecting fourth century debates or parsing the bishops’ language in attempting to resolve their church crisis. What happened in 325 is not simply an historical object of scholarly examination, but a rule of faith that continues to provide the now-divided church with a dogmatic consensus that binds church communions and denominations, formally or informally. Tertullian wrote that as long as the church held to the rule of faith it was free to seek and discuss and satisfy its curiosity. But the Nicene rule of faith itself does not function apart from its liturgical and pedagogical home. When the Creed is ignored, taken for granted, disregarded, or dismissed, curiosity will lead in strange directions.

We Believe in One God

In a twenty-first century ecclesial culture that turns away from its own history, most Christians encounter the Nicene and Apostles’ Creeds, if at all, in worship. Even there some experience the Creed as burden rather than gift. Kathleen Norris expresses a common sentiment when she writes, “Of all the elements in a Christian worship service, the Creed, by compressing the wide range of faith and belief into a few words, can feel like a verbal straight jacket.”[13] For many, the recitation of the Creed can become merely customary, words spoken indiscriminately so that while the form remains, their substance is reduced to a shadow. Pastors may omit the confession of faith altogether because the Nicene Creed is too long and there are other, more important things to squeeze into an hour.

Luke Timothy Johnson gives voice to the way beyond seeing the Creed as burden, custom, or inconvenience. “The church today desperately needs a clear and communal sense of identity,” he says. “What does it mean to be Christian?”[14] He goes on to say that “the Creed challenges every member of the community and places demands on them. The Creed expresses what and how the church believes more and better than I do. Therefore it calls me to a level of belief and practice that is now beyond me.”[15] The Nicene Creed begins “We believe,” not because every person who speaks it believes every word, but because it articulates the faith of the church which we are called to make our own. Furthermore, it does not say allthat it means to be Christian, but it does define the essential core of the Faith, providing boundaries that are not barriers, freeing us to know and participate in the mission of God.

The Nicene Creed opens with what may appear clear and obvious: “We believe in one God.” Those five words are the taken for granted presupposition of everything else in the Christian faith. However, when the Creed begins by confessing faith in one God, it is generally assumed that everyone knows what is meant when the word “God” is uttered. Preaching and teaching as well as confessing proceed in the naïve belief that “God” is intended and heard the same way by speaker/hearer and writer/reader. But a moment’s reflection is enough for us to know that “God” is a word that is filled with many meanings, ranging from the faithful to the instrumental and sentimental to the bizarre.

Popular culture both reflects and shapes understandings of “god” among Christians. Movies and television portray god as a humorous meddler or a helpful intervener who solves personal problems. In sequential versions of “the power of positive thinking” and “the health and wealth gospel” god is represented as the benign power to fulfill everyone’s wishes. Social historian Charles Lippy traces a generic American religiosity that sees god as a divine power directly available to ordinary people, tapping a reservoir of latent power within the self.[16] God can also be seen as the power to achieve social and political aims. None of this is new or unusual. Calvin characterized human nature as “a perpetual factory of idols,”[17] for the constant human temptation is the effortless creation of a god made in our image.

Everything that follows from the opening words of the Creed fills the word “God” with a rich array of biblical narratives, poetry, indications, limitations, similes, metaphors, and pictures. The Nicene Creed first gives faithful content to the word “God” by naming God “One, Father, Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, of all there is, seen and unseen.” These are not definitions of God, but namings of God.

Then Moses said to God [Elohim] “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘the God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘what is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM [YHWH].” And he said “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘I AM [YHWH] has sent me to you” (Ex 3:13–14).

What is in a name? Moses asked who what, when, where, why, how are you, God? The answer to Moses’ question and to ours lies in the narrative of God’s presence with Israel and in Christ. The creedal words “Father, Almighty, Maker,” and the stipulations “of heaven, earth, all things, seen and unseen” are filled by the actions of God in the life of a people and in their experience articulated in praise, prayer, and action of their own. The Creed points to what we know of God in the Tenach—the Torah, Prophets, and Writings of the First Covenants. The Creed also points to what follows, for Father is correlative with Son.

What does the opening of the Nicene Creed refuse? False gods, of course––not only images in stone and wood, but images that dwell in the minds of those who exchange the scriptural record of God’s presence for cultural myths of our own imagining. Karl Barth made this clear. “Our knowledge of God,” he wrote, “could so easily be an empty movement of thought if in the movement which we regard as the knowledge of God, we are really alone and not occupied with God at all but only with ourselves, absolutizing our own nature and being, projecting it into the infinite, setting up a reflection of our own glory. Carried through in this way, the movement of thought is empty because it is without object. It is a mere game.”[18]

The Nicene Creed is scriptural, not by quoting verses, but by employing namings of God that point us to God’s way in the world and among his people. Again, Barth makes the point well: “The [biblical] passages which speak expressly of the uniqueness of God are only in a sense the spokesmen for a far more extensive conception of the uniqueness of the form and content of the events between God and man in which the being of God as the one and only God has been revealed.”[19]

We Believe in One Lord Jesus Christ

The Nicene Creed unfolds belief in the Lord Jesus Christ in two interdependent ways. The first of these is in response to the Arian contention and its contemporary successors. It addresses the central issue: Is the Son of the Father truly God as God is God? Nicaea’s elegant words are employed to drive the point that the Son of God is, indeed, one with God the Father.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father;

through him all things were made.

The language used to refer to Jesus Christ flows directly from the language used of God—believe … one … Lord … only … Son … eternally … all things made. Our way of referring to three ‘articles’ of the Creed is a misleading convenience. What is intended as a seamless whole, easily becomes understood as three separate statements. Nicaea is one creed, and therefore language used of the Holy Spirit also echoes language used of the Father and the Son—Lord … giver of life. Each of the ‘articles’ only proclaims its truth in fullness when it is confessed integrally with the other two.(The PCUSA’s “A Brief Statement of Faith,” intended for use in worship illustrates the problem. Not brief enough to be confessed in whole during worship, it is suggested that “trust in Jesus Christ, trust in God, and trust in God the Holy Spirit” can be used separately in worship, beginning and concluding each with the Statement’s opening and closing lines.)

The Nicene Creed elegantly articulates the unity of Father and Son: “God from God, Light from Light, true God from True God.” Lest the little preposition “from (ek in Greek) be misconstrued as indicating priority, the Creed stresses the positive true God and then makes two crucial distinctions. First, the Son is not made, that is, not one of the “all” that God has made, in heaven as well as on earth, unseen as well as visible. But what does it mean to say begotten not made? What is the difference? Clearly, the intent of “not made” eliminates the Arian assertion that “there was a time when the Son was not,” and therefore a lesser, created being. But what, then, is the contrary assertion that the Son of God was begotten? The technical use of the term is elusive, but the intention is to underscore Father-Son unity in distinction from a maker-created inequality.

The Son bears the essence, the fullness, the Being of the Father. The technical articulation of the difference between Arians and the Creed hinges on the little Greek letter iota, the equivalent of the English i. In Greek the word homoiousios is translated “similar being (Arian contention) while its absence is translated “same/one being” (language of the Creed). While homoousios is not a biblical concept, the use of philosophical terminology that the Son is “of one Being with the Father” summa-rizes the prior “God from God, light from light, true God from true God” sequence. The “begotten, not made” distinction is then sealed with the biblical proclamation that it is through the Lord Jesus Christ the Son of God that “all things were made,” unmistakably identifying the Son with God the Father Almighty, maker of all things.

The following sequence of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ moves the Creed into more familiar biblical language:

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

was incarnate of the Holy Spirit

and the Virgin Mary

and became truly human.

For our sake he was crucified

under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

The remarkable feature of the familiar recitation of Jesus Christ’s birth, life, crucifixion, resurrection, ascension, and return is that it was all for us and our salvation and, again, for us. The Creed not only rehearses the past and the hoped-in future. It shows all of it as a present reality for us, here and now. Who is the “us”? The bishops gathered at Nicaea were not the “us,” as if they were announcing their special access to the grace of Christ. Nor is the “us” confined to Christians, for the “coming down from heaven” was to become “truly human” for the sake of all humankind. Surely Christians know what others do not, that it was all for them as well. The mission of Christians is to proclaim that good news to all who do not know that Christ is, for the sake of their salvation, for them. What Nicaea did not need to specify, and Christians today need to understand more fully and to proclaim more adequately is what is meant by “salvation.”

A second notable feature is that the Nicene Creed, like the later Apostles’ Creed, makes it clear that Christ was “crucified under Pontius Pilate.” If anyone is to be called “Christ killers” it is Rome, not the Jews. That the bishops placed responsibility on the Empire while in the presence of the Emperor may be an indication that Constantine was not in control of the council. A third notable feature is Nicaea’s acknowledgment that its credal recitation is “in accordance with the Scriptures.” Non-creedal churches sometimes assert, “No creed but the Bible.” Yet, in the Arian controversy, and in many controversies since, Scripture itself has been the point of contention, with various persons and groups appealing to the Bible to support their views. Differing interpretations of Scripture may be harmless, helpful, or clarifying, leading to a deepening of the church’s faith and faithfulness. Some, however, may threaten the church’s fidelity, necessitating renewed statements and confessions that are “in accordance with the Scriptures.”

We Believe in The Holy Spirit

The Nicene Creed of 325 clarified the unity of God the Father and God the Son, but it concluded with the almost offhanded, “. . . and the Holy Spirit.” There was no affirmation of the Spirit’s divinity or even mention of the Spirit’s works. The church had always assumed the continuing presence of the Holy Spirit in its life— teaching, inspiring, and sanctifying its members, priests, and bishops. But it was inevitable that the Arian controversy would provoke a parallel debate about the full divinity of the Spirit. Athanasius, the great defender of Nicene orthodoxy, wrote that the Arian heresy “speaks against the Word of God, and as a logical consequence profanes His Holy Spirit.”[20]

In the decades that followed the council at Nicaea, Arians attacked the Sprit’s divinity, earning for themselves the epithet pneumatomachoi, “fighters against the Spirit.” Basil the Great voiced the seriousness of the matter before the church: “All the weapons of war have been prepared against us; every intellectual missile has been aimed at us . . . But we will never surrender the truth . . . The Lord has delivered to us a necessary and saving dogma: the Holy Spirit is to be ranked with the Father.”[21]

Orthodox theologians ranked the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son, yet they never applied the term homoousios to the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Christ. Instead, traditional narrative language was employed to account for the Holy Spirit’s movement in the life of the church and lives of the faithful. “I reckon that this glorify- ing of the Holy Spirit is nothing else but the recounting of His own wonders,” wrote Basil. “To describe His wonders gives Him the fullest glorification possible.”[22]

When the second Ecumenical Council met at Constantinople to supplement the Creed established at Nicaea, it added the paragraph on the Holy Spirit, giving us the complete Nicene Creed that we know today. What might appear to be an affirmation of the oneness of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son, followed by a list of doctrinal leftovers, is actually a biblical narration of the work of the Spirit.

We believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life

who proceeds from the Father,

who with the Father and the Son

is worshiped and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic

and apostolic church.

We acknowledge one baptism

for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come.

Continuity with the original Creed of Nicaea is apparent in the use of Lord (We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ) and giver of life (We believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth). As the Father and the Son are worshiped and glorified, so too is the Holy Spirit. Even more is intended, however. If the Creed had concluded with the narrative of Christ’s coming for us and our salvation it would have left a void between Christ’s ascension and his promised return. But the ongoing reality of God-with-us is the presence with us in the work of the Holy Spirit.

Shortly before his death Jesus assured his disciples, “I will not leave you orphaned.” He promised the continu-ing presence of “another Advocate to be with you forever. This is the Spirit of truth . . . You know him, because he abides with you, and he will be in you.” (John 14:16–18) The Nicene Creed articulates God’s continuing presence with humankind as the Holy Spirit abides with, among, and in humankind. The Spirit reveals the truth about God’s Way in the world, creating new human community, empowering the people of God, nurturing the church in faithfulness, and leading us in faith, love, and hope.

The Creed’s narrative of the Holy Spirit proclaims the continuing action of the life-giving One who spoke and speaks through the Scriptures, who forms the Christian community and shapes its character, who unites us to Christ’s death and resurrection, who seals, forgives, and creates new life within us, and who fills us with hope for ourselves and all creation. Calvin, writing centuries after Nicaea, sums it up well: “Thus through the Holy Spirit we come into communion with God, so that we in a way feel his life-giving power toward us. Our justification is his work; from him is power, sanctification, truth, grace, and every good thing that can be conceived.”[23]

The Nicene Creed’s narrative of the Holy Spirit includes faith [belief, trust, fidelity] in the “one holy catholic apostolic church.” What that meant to the bishops of the Council of Constantinople as they supplemented Nicaea in 381 made sense in an era of the one church, but its contemporary significance is elusive. Our reality is radically different. When we look at the church we see not unity, but division into thousands of churches; not holiness, but conformity to cultures; not wholeness, but fragmented geography, race, class, and gender; not mission, but distance from apostolic tradition and confinement to institutional preservation.

Recourse to notions of the invisible church is not sufficient to overcome visible departures from the Nicene marks of the church. When the only church we can experience is divided and divisive, worldly and flawed, partial and restrictive, self-absorbed and unresponsive, then the Creed’s testimony becomes for us not affirmation but judgment. One of the enduring gifts of the Nicene Creed is to call the contemporary church to repentance for faithlessness. However, repentance is turning around to see the work of the Holy Spirit among us. It means refusing to limit understanding of the Spirit’s work to casual confirmation of ecclesiastical decisions or spiritual blessings for individuals. It means recovering faith in the One who is now the Lord and giver of life, who speaks now through Scripture, who now unites us to Christ in baptismal life, who now can fill us with hope in the triumph of God.

“A diseased organization cannot reform itself,” says the mid-twentieth century satirist of business organizations, C. Northcote Parkinson. “The cure,” he wrote, “what-ever its nature, must come from outside.”[24] The Nicene Creed calls the church to forswear its self-reliance and believe once again in the power of the Holy Spirit.

The Nicene Creed: 2026 and Beyond

Serious, sustained attention to the Nicene Creed is an urgent task in our time and place. If marking seventeen hundred years of the Creed becomes little more than a fleeting blip on the churches’ radar screens, we will have lost a significant occasion for renewal of our faith and life. In a diverse, highly segmented American society, patterns of belief are no longer shaped by articulations and associations. Convictions and actions have become matters of individual choice and private decision. There are no paths that people must follow or authorities to which they are accountable––whether families, or advisors, or systems, or institutions. Instead, individuals assume that they are the authority deciding which of the multiple possibilities to choose.

What is true of our culture is true in the church. Ameri-can churches are no longer communities of shared certainty in commonly acknowledged truths. The church has never been a uniform community of unanimous views, of course. Even a casual reding of the New Testament letters is enough to recognize that the church has been characterized by diversity from the beginning. Yet the New Testament letters assume that, within the matrix of rich human diversities, unity in faith and life is the central intention for the Christian community.

In a pluralistic church, study of the Nicene Creed together with regular use in worship is an essential task. Its goal is certainly not to impose dogmatic formulations or compel assent to institutional orthodoxy. Instead, common attention to the Creed can engage Christians in a shared search for the truth about God and ourselves––truth larger than ourselves that can liberate us from idolatry and self-deception, truth that can set us free to live in love for God and neighbors. The Nicene Creed is especially suitable for shared inquiry because it has been the most universal expression of Christian faith for seventeen hundred years. Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant churches have joined their voices to confess Nicaea’s apostolic faith. The primacy of time and space gives the Nicene Creed a claim on our attention.

Shared inquiry, in 2026 and beyond, need not be confined in single congregations or denominations. Neighboring congregations and their pastors can study together, denominations can encourage regional studies, especially among recently divided communions. Amid the accumulated wreckage of historic, theological, and ethical battles lies the received heritage that we are called to confess together: We believe in one God . . . the Father the Almighty . . . one Lord Jesus Christ the only Son of God . . . the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life.

[1] The line is from Faulkner’s play, “Requiem for a Nun.”

[2] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics I/2 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1956), 631.

[3] Christopher Morse, Not Every Spirit: A Dogmatics of Christian Disbelief (Valley Forge: Trinity Press International, 1994), 3–4.

[4] Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Book of Confessions (Louisville: Office of the General Assembly, 2016), 283.

[5] Book of Confessions, 303.

[6] Book of Confessions, 248f.

[7] “The Confession of the Arians Addressed to Alexander of Alexandria” in Christology of the Later Fathers, ed. Edward R. Hardy (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1954), 322.

[8] “The Confession of the Arians,” 323.

[9] “Encyclical Letter of Alexander of Alexandria and His Clergy,” in A New Eusebius, ed. J. Stevenson (London: SPCK, 1965), 343.

[10] See, among others, Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee (San Francisco: Harper One, 2014).

[11] Irenaeus, Against the Heresies, 1.10.1., in St. Irenaeus of Lyons, Ancient Christian Writers 55, ed. Walter Burghardt (New York: Newman Press, 1992), 48f.

[12] Tertullian, “Prescriptions Against Heretics,” 13, in Early Latin Theology, ed. S.L. Greenslade (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1956), 39.

[13] Kathleen Norris, Amazing Grace (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998), 205.

[14] Luke Timothy Johnson, The Creed (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 297.

[15] Johnson, The Creed, 301.

[16] Charles H. Lippy, Being Religious American Style (Westport CN: Praeger, 1944).

[17] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Ford Lewis Battles (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960) 4.1.4., 1016.

[18] Barth, Church Dogmatics II/1, 71. Translation revised.

[19] Barth, Church Dogmatics II/1. 454.

[20] Athanasius, “Letter to Maximus” (c. 371), in Nicene and Post–Nicene Fathers, vol. 4, ed. Philip Schaff & Henry Wace (Peabody MA: 1892/1944), 567.

[21] St. Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit (Crestwood NY: St. Vladimir’s Press, 1997), 10.25; 45f.

[22] Ibid., 23.54; 86.

[23] Calvin, Institutes 1.13.14., 139.

[24] C. Northcote Parkinson, Parkinson’s Law and Other Studies in Administration (New York: Ballentine Books, 1957), 110.